Design may be our specialty, but that doesn’t mean we don’t love a bit of fine art, too. The creativity that goes into making a work of art inspires us and whenever we’re feeling a bit stale we love a visit to one of Edinburgh’s many museums to get our creative juices flowing again. From the Middle Ages to the Renaissance, Baroque to Modern, if it’s art, we’re into it—and there’s nothing we love more than a good art-related story. Whether it’s a mysterious provenance, a lost work, a crime gone wrong (or gone right), we’re always keen to learn more about the art world and its most important works. Here are some stories we’re paying attention to these days along with a few faves from the past:

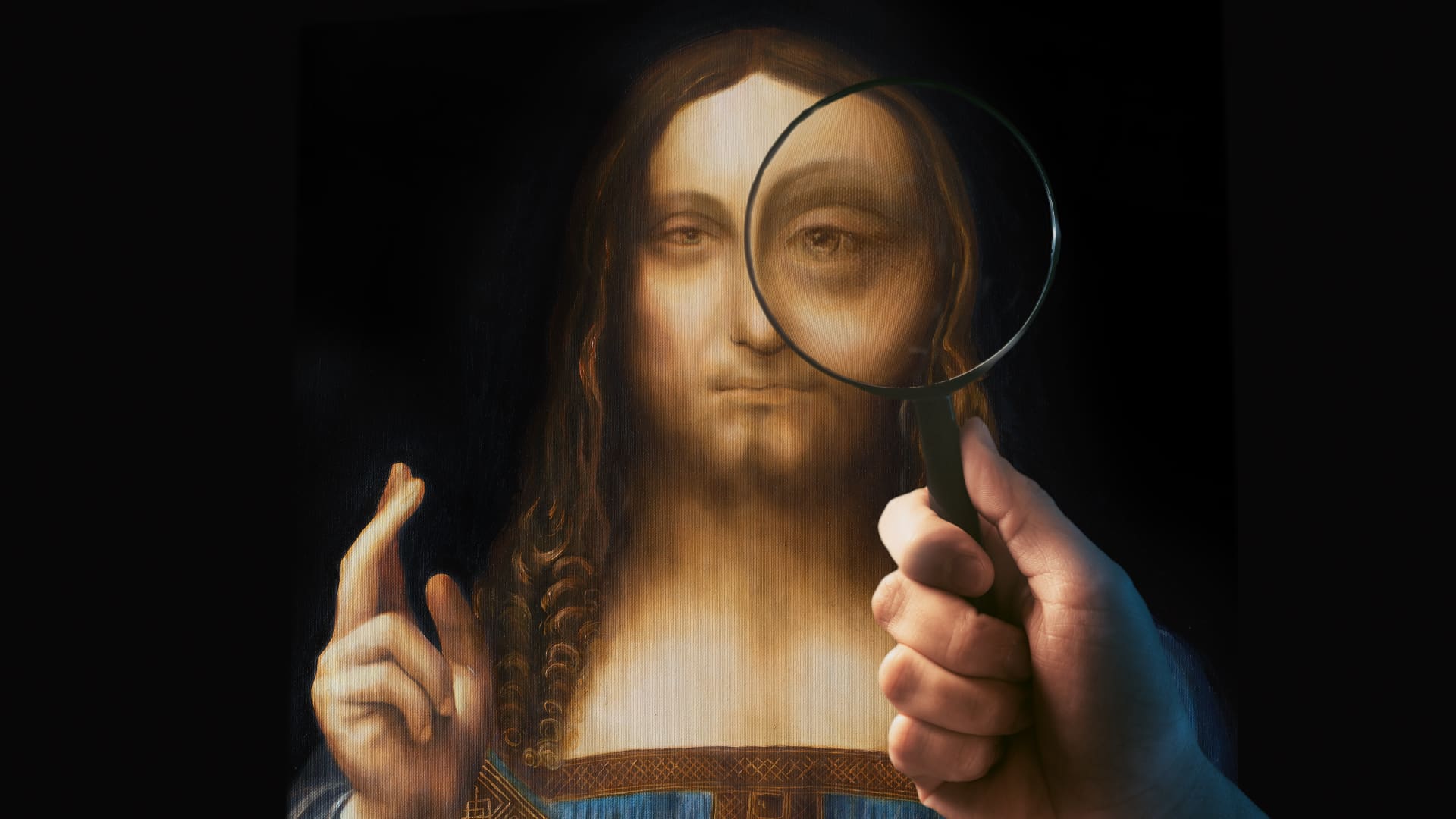

Salvator Mundi | Leonardo da Vinci, c. 1500

Let’s start with a piece that’s making headlines right now: Salvator Mundi, by Leonardo da Vinci (probably) is no stranger to setting records. It was lost for a century then found and purchased for the modern-day equivalent of roughly £1,000 in the mid-1950s. With a mixed provenance and questionable veracity, it eventually went to the auction block in 2017, where it set a world record of $450Million, a whopping 50% higher than the previous record. As with most high-end art purchases, the auction house originally concealed the identity of the buyer, but soon it came out that the purchaser was a surrogate for the Crown Prince of Saudi Arabia. Shortly after the purchase, the Louvre Abu Dhabi announced that the painting would soon go on show and had become part of their permanent collection, but the exhibition never happened, all mention was removed from the museum’s website and the painting still hasn’t been shown anywhere. It’s now missing, and neither the Louvre Paris nor the Louvre Abu Dhabi know its current location. AWOL for nearly two years, it’s a world treasure that we still hope goes on public view soon.

Canyon | Robert Rauschenberg, 1959

Canyon epitomises all the philosophical clichés you can think of: it’s an immovable object (a bald eagle) met by an unstoppable force (the US government). It’s a work stuck between a rock (millions of dollars in taxes) and a hard place (an unsellable painting). If a tree falls in the woods, can you break the law to pay off your estate taxes?

Ok ok, let’s back up. Robert Rauschenberg, known for his post-modern, Neo-Dada & Pop Art, created this piece in 1959. It contains a taxidermied bald eagle emerging from the canvas, and therein lies the problem: in the US, it has been illegal to sell a bald eagle, whether alive or dead, since 1940. Rauschenberg was able to gain permission to use the eagle in his work because it had been killed and stuffed by one of Teddy Roosevelt’s Rough Riders decades before the law protecting eagles went into effect, but that didn’t save the inheritors of the painting, who acquired it in 2011 from the artist’s dealer.

Because it’s illegal to sell the work, appraisers hired by the heirs valued it at $0. But because it’s a priceless work by one of the most well-known artists of the twentieth century, the US government appraised it at $65Million, and requested taxes in the amount of $29Million. The heirs were thus faced with a catch-22: either they sell the work and go to jail so that they can pay the taxes on it, or they keep the work and go to jail for not paying taxes on it—oh, and worst of all, they couldn’t even donate the painting without paying taxes, so truly there was no way out for them. After several years of legal toil, the government reached an agreement with the heirs and allowed them to donate it to the Museum of Modern Art in New York, but not without a fight so well-known it’s mentioned in the museum’s own accession information about the painting.

Adoration of the Mystic Lamb | Hubert & Jan van Eyck, c. 1432

Better known as The Ghent Altarpiece, this work has been taken, hidden, and reinstated in its home at St Bavo’s Cathedral more frequently than any other work of its calibre, falling victim to a total of thirteen crimes and seven thefts during its nearly-600-year history, most recently when it was looted by the Nazis during World War II. So what’s the big deal now? Well, pre-WWII, 2 panels from the massive altarpiece were stolen in the 1930s. One was returned soon after, but the other has never been recovered. Just last year, though, a furore erupted when two authors released a book claiming to have solved the code left by the thieves that gave away the location of the missing panel. So sure were they that they had found the correct location (underneath a square in the middle of the city), and so intent on recovering the panel, that the mayor of Ghent had to release a statement requesting that the people of Ghent not take shovels and pickaxes to the ground in the middle of the square.

It’s been a year now since the book came out with a mystery so complex it reads like a Dan Brown novel. So far the missing panel still hasn’t been recovered, but it feel tantalisingly close given the clues that have emerged in recent years. One thing is for sure: the altarpiece has survived far worse than this, so with any luck the missing piece will be recovered before the masterpiece turns 600.

The Crucifixion | Pieter Breughel the Younger, 1617

Known primarily as a copyist of his father’s work, Pieter Breughel the Younger’s work was mainly ignored until the early twentieth century, when it was finally given its due. His Crucifixion, owned by the church of Santa Maria Maddalena outside Genoa, was recently stolen from the glass case where it was displayed in the church… or was it? Shortly after the theft, the mayor of the town where the painting was displayed held a press conference to announce that the work had not actually been stolen—in fact, the police heard rumours that a pair of art thieves were planning a heist, so they swapped out the painting for a replica, installed security cameras and swore the churchgoers who noticed the false painting to secrecy. The true painting is safe, and hopefully the extensive press this story received will keep similar thieves from attempting similar capers in the future.

The Honours of Scotland | before 1543

Let’s finish with something a little bit closer to home. The Honours of Scotland, like crown jewels from many countries, have a complicated back story. They’ve been hidden and recovered three different times, most recently during World War II, but the most interesting recovery was in 1818 by Sir Walter Scott. The exact location of the jewels had been forgotten since the Act of Union in 1707, but writer, historian and all-around Scotophile Sir Walter Scott received permission from the King to knock down a false wall in Edinburgh Castle to search for them. He found a chest that contained all of the Honours, exactly as they had been left more than half a century before, except for one thing: there was an extra item in the chest. As he examined the crown, sceptre and sword, Scott realised there was also a wand included with the Honours. The wand is silver gilt, a metre long and topped with a crystal and a cross. There are no records of the item prior to Scott’s discovery of it, and the purpose has long been forgotten—but that doesn’t stop the speculation. Could it have been carried before the Lord High Treasurer? Or perhaps it belonged to the Lord Lyon? Maybe someday we’ll solve the mystery—but only if a new painting or trove of records is uncovered. In the meantime, the wand is displayed at Edinburgh Castle in the same room as the rest of the Honours, but in a separate case from the crown, sceptre and sword.

We love art and the stories that surround the most captivating works, but our creative passion is design, of course. Looking for design or branding help for your business? Contact us today!