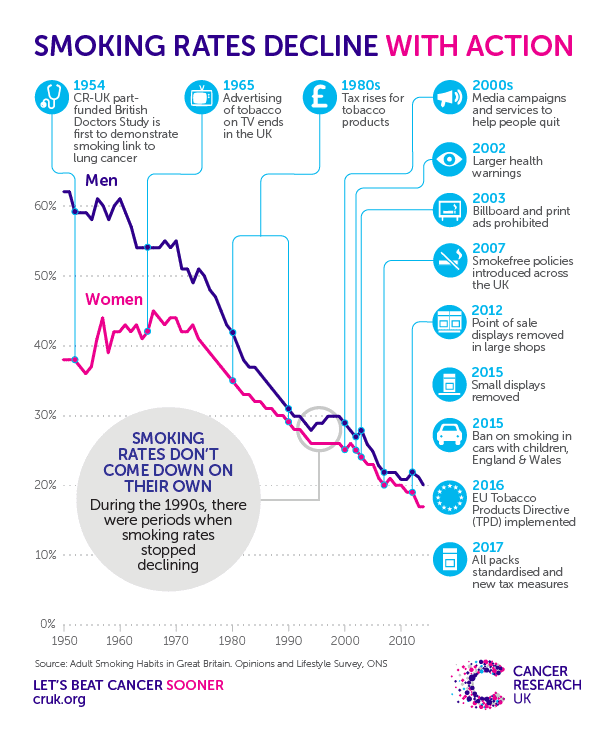

Cigarette ads seem like a thing of the past: Gen X and millennials weren’t even born when ads for cigarettes were banned on UK television back in 1965, and indeed most millennials don’t remember a time when smoking ads were allowed anywhere. Tobacco restrictions aren’t just guidelines provided by the ASA: there are actual laws that prohibit all forms of tobacco advertising and make it exceptionally difficult to reach new smokers, strangling tobacco companies’ profit margins by limiting their target audience.

While it’s inarguable that marketing (or a lack of it) contributed to the significant drop in smoking rates over the past decades, it’s not the sole cause of this decrease. Improved education, better scientific understanding, government-subsidised cessation programmes, restrictive laws and new products to help users quit have contributed to a drop in total numbers of smokers just as much (if not more) than the lack of public-facing marketing. Rates of new smokers, though, saw large drops every time a law was put in place banning cigarette advertising. The government hopes to continue the drop in new smokers by making smoking more and more inconvenient, expensive and off-putting, along with keeping it from being top-of-mind for young people. And while predictions of a total eradication of smoking have been swirling for generations, there’s a new player in town that might derail those hopes.

E-cigarettes, non-tobacco, non-‘smoke’ products, burst onto the scene back in 2004, but didn’t really gain popularity in the West until around 2010. As with most new forms of technology, the popularity surged while governments and regulatory bodies scrambled to catch up.

In the US, the teen smoking rate is at an all-time low of <5%, a decrease of a whopping eighty percent in 18 years, from 23% in 2000. Compare this to the 1980 rate of teen smoking, which was… basically the same as the 2000 rate, showing no significant decline in the 20 years before 2000. These figures, though, don’t take e-cigarettes into account—and this matters a lot: e-cigarette use among teens is now at the same level as cigarette use was in 2000.

The boom in popularity goes hand in hand with the difficulty in regulating e-cigarettes. E-cigarettes, particularly when they debuted, were touted as a safer alternative to tobacco: because there were no laws surrounding their production and very little knowledge about their ingredients, it was easy for manufacturers to promote them as ‘safe.’ As watchdog groups and governments learned more about them, the truth became clear. The ingredients in e-cigarettes may be different than the ingredients in tobacco cigarettes, but they’re still toxic: propylene glycol (the ingredient ‘used in anti-freeze’ that sent the internet into waves of panic when it was reported), nicotine, heavy metals, VOCs, ultra-fine particles, and of course the widely-maligned formaldehyde are all components of e-cigarette vapour, including often overlooked secondhand e-cigarette vapour.

In addition to manufacturers choosing to ignore the dangers of e-cigarettes, their branding also helped them reach a young audience quickly and at scale. The products are easy to make appeal to a young audience: with flavours like whipped cream, cookie dough and bubble gum in packaging that looks like snack food, of course teenagers are interested in it.

Perhaps the biggest danger of e-cigarettes (as well as a reason for their popularity), though, is that thanks to manufacturers promoting them as ‘smoking cessation aids,’ many people still think of them as useful tools to leverage in the arsenal against smoking. But according to many leading scientific organisations, there are no e-cigarettes that help people quit smoking. The damage has already been done, however. Thanks to marketing campaigns promoting e-cigarettes as a useful tool to quit smoking, many people simply switched from cigarettes to e-cigarettes without ever making the leap to actually quit.

So with all that information about their hazards, why were e-cigarettes allowed to be advertised at all? Well, they’re not actually cigarettes, so they didn’t fall under the tobacco law (meaning they could be marketed with flavours and packaging that appeal strongly to young people & teens). They’re not ‘tobacco accessories’ like filters and rolling papers, so they weren’t restricted there, either. Marketers embraced this loophole and promoted them with abandon until 2016 that the Tobacco & Related Products Regulations 2016 came into effect here in the UK, but by then the government was already backfooted, facing a meteoric rise in youth e-cigarette adoption without much of a way to stop it.

Many traditional methods of enticing youth away from smoking don’t work with e-cigarettes, either. Since they’re widely (though falsely) viewed as being safe, it’s hard to scare people out of taking up the habit. They don’t smell as strong as cigarettes, so that argument is out. Because many bars and public places haven’t expressly forbidden their use, they’re able to be used in more places than tobacco, so it’s hard to convince new users to avoid them for social reasons. In many places, they’re also more cost-effective than traditional cigarettes, with a standard e-liquid cartridge containing the same amount of nicotine as a pack of cigarettes, but costing only ¼ as much.

All of this has led to massive profits for e-cigarette manufacturers. Back in December, tobacco brand Altria purchased a 35% stake in Juul, resulting in a $2Billion dividend split among Juul’s employees at a rate of over $1Million per employee. The US government has their eye on this deal, though, and started an investigation into Juul and their marketing practices this month. Back in 1998, a similar government investigation and subsequent class-action lawsuit resulted in tobacco companies in the US paying $206Billion to the government over 25 years to pay for healthcare costs relating to smoking as well as to run campaigns to prevent youth smokers. Is the same in the pipeline for e-cigarette manufacturers? Quite possibly. In the meantime, though, e-cigarette manufacturers would be wise to play by the rules if they want to avoid government or advertising watchdog trouble.