Lee Miller (1907-1977) succeeded at anything she set her mind to… and she set her mind to a lot over the course of her life. Model-turned-artist-turned-journalist, her work has been celebrated in a variety of media and continues to receive accolades over forty years after her death.

Frequently credited only as ‘muse of Man Ray,’ I first became interested in her story because I was convinced she must have had a more interesting story than that. While studying for my master’s degree, I learned more about her own life and how sharply it contrasts with the reductionist characterisation of her as the inspiration for works of art by someone else.

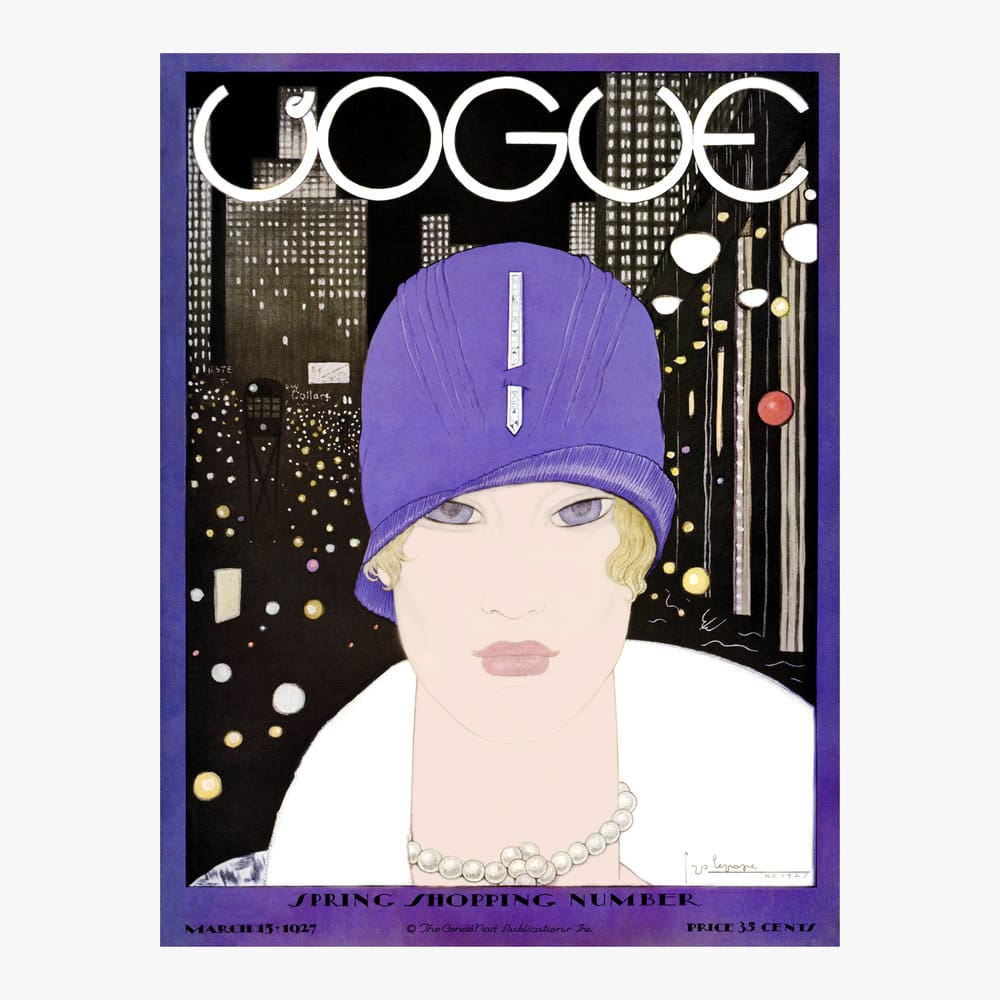

Miller got her professional start as a model in the 1920s when Condé Nast (the magazine mogul) spotted her. She was on the front of Vogue months later at the age of only 19. From there, her modelling career began to take off… until, unbeknownst to her, a photographer sold a photo of her which he had taken to Kotex. Kotex used the photo in an ad, making Miller the first person ever featured in a sanitary product ad. Such were the social mores of the time, though, that this ended her career before it had really gotten off the ground.

Vogue Magazine, March 1927. Cover illustration: Georges Lepape.

Determined not to let this insult end her professional aspirations, she took a job painting Renaissance art details for a fashion designer, but she was bored. Never one to rest on her laurels, she decided to learn photography, left the US for Europe and convinced Man Ray to teach her how to use a camera. For half a decade, she was one of the It-Girls of the Surrealist movement in Paris, associating with artists like Salvador Dalí, Pablo Picasso and Max Ernst. She wasn’t just a studio assistant, though: she was a model for the other artists but also a photographer in her own right, talented enough to open her own photography studio in the early 1930s.

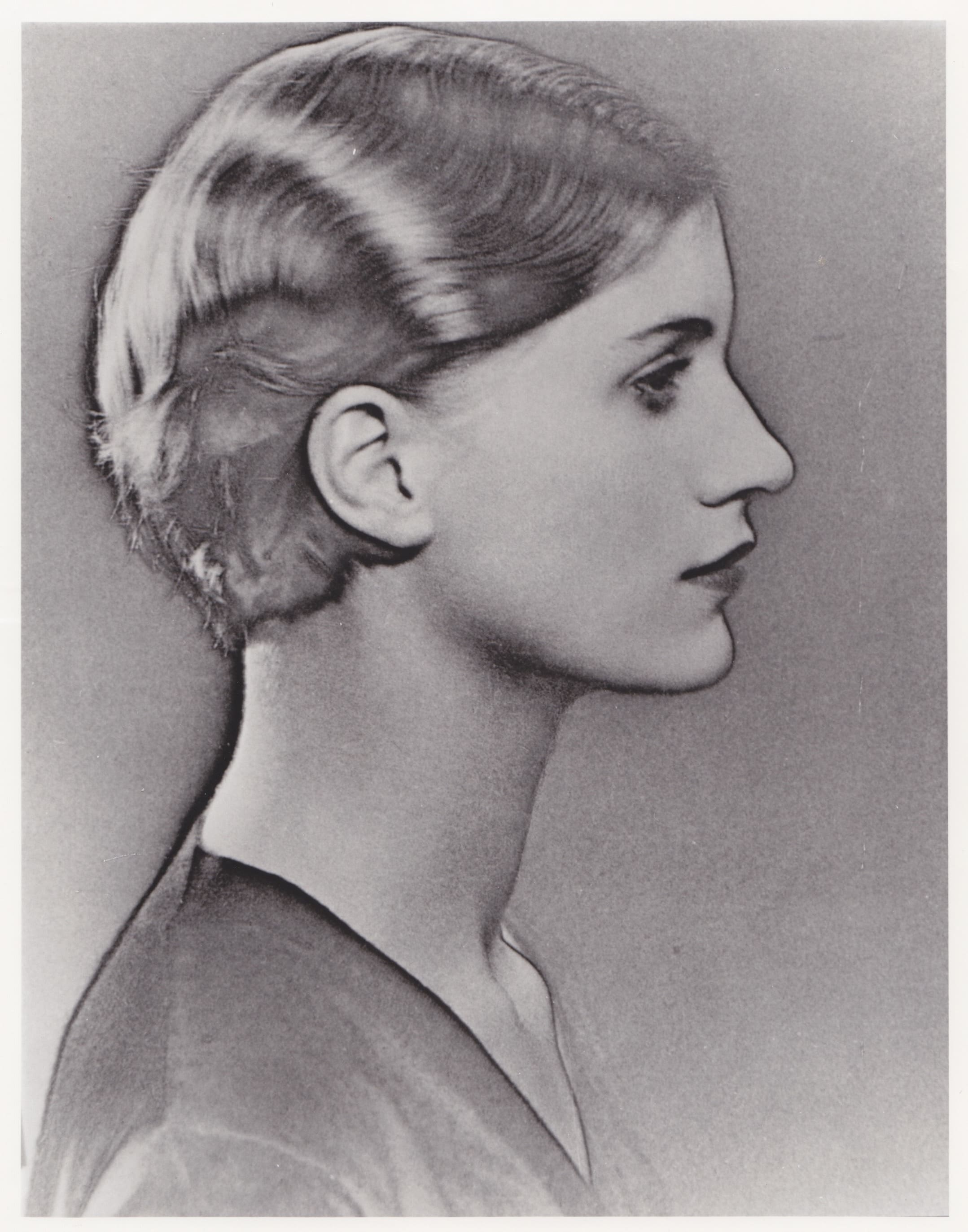

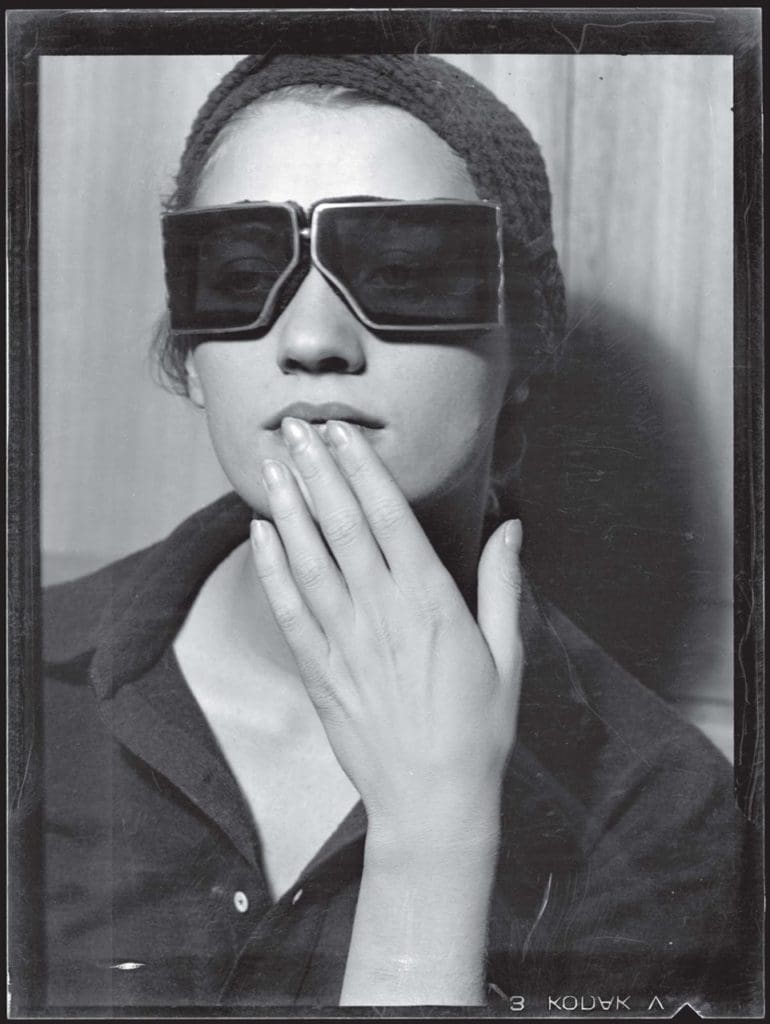

Solarised Portrait of Lee Miller, Man Ray. 1929, The Penrose Collection.

But then World War II broke out, and instead of fleeing back home to the US, she remained in London, documenting the Blitz from a first-hand perspective. By December 1942, a year after the US had joined the war, Miller secured credentials as an embedded journalist for Vogue—the only female combat photographer in the European theatre (it’s worth noting that when she first applied, the magazine turned her down in favour of renowned photographer Cecil Beaton). Miller knew that as a woman in a combat zone, she’d need to work just as hard as (if not harder than) the male soldiers she travelled with, but—and here’s what I love about her thinking—she also knew that as a woman she’d be given opportunities to see things that the men with her would not. She thus faced somewhat of a double-bind: Miller needed to be ‘one of the boys’ when she was with the soldiers, but she also needed to set herself apart as a woman—with all the sensitivity and empathy that implied—when she encountered photo subjects in the towns she visited.

Portrait of Lee Miller, Man Ray.

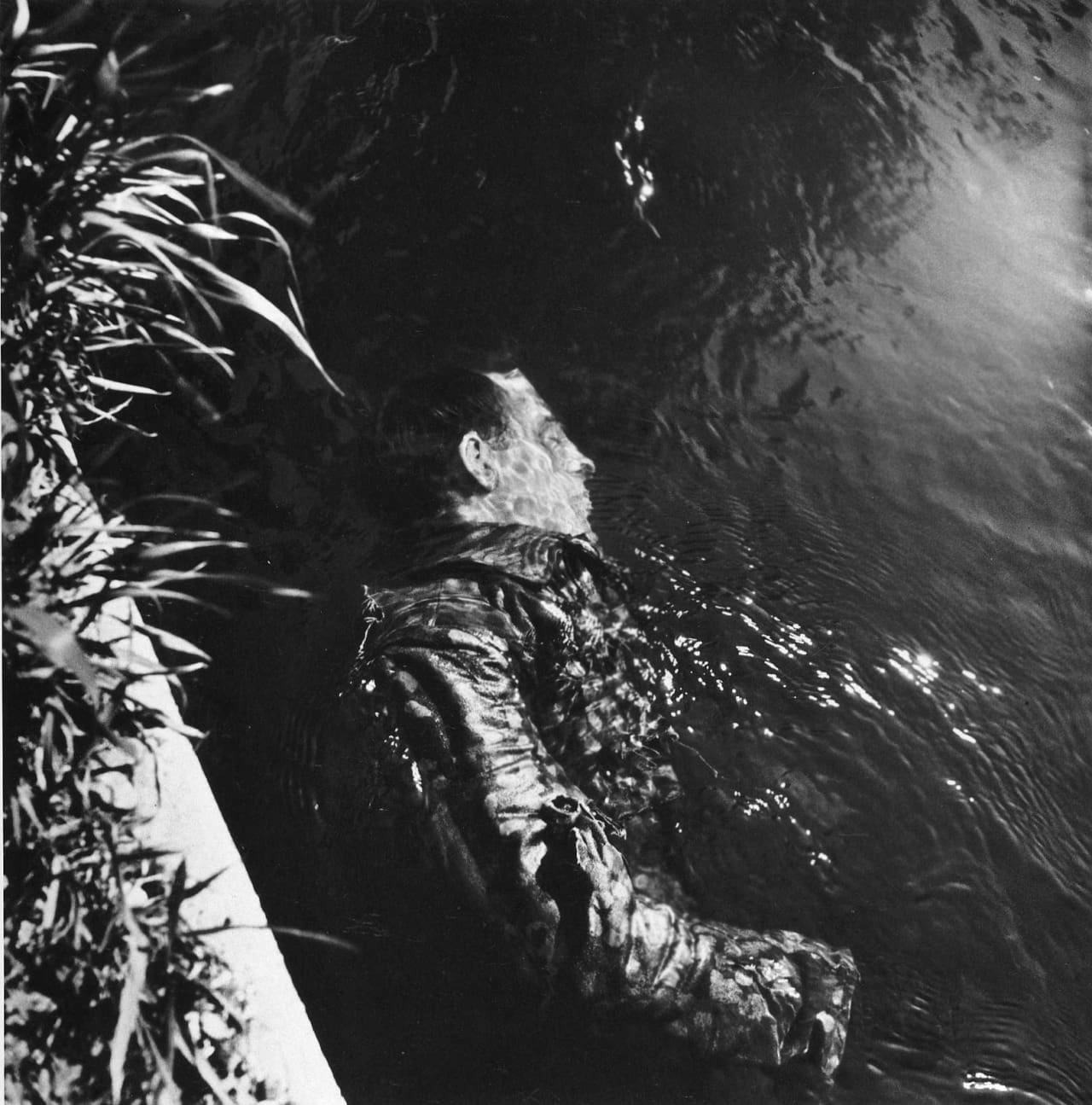

Her photos from the period show a remarkable level of nuance, particularly in comparison to the many men who were also documenting the war in Europe. The most famous photojournalists of the period (men like Robert Capa, Edward Steichen and Joe Rosenthal) used the frontline access they were afforded by virtue of their gender to document battles and action scenes as they happened. Miller, who was the first woman in Normandy after the Allied invasion, still arrived almost a month after D-Day—not exactly the same timing as Capa, who was present on the day of the invasion. What should have been a disadvantage to Miller, though, she turned into an advantage, using her access to document the destruction of war and the devastation of the people and towns left behind.

Dead SS Prison Guard Floating In Canal, Lee Miller, 1945.

Not one to let her gender hold her back, by the time the Allies reached Germany, she had fought her way to the frontlines and was present at the liberation of both Buchenwald and Dachau concentration camps. Shortly after the liberation of Dachau, she headed to Munich, where she was the first person to enter Hitler’s empty apartment, documenting the experience by photographing herself taking a bath in his tub—first making sure to wipe her muddy boots all over the clean bathmat. Vogue, meanwhile, didn’t really know what to do with the photos she submitted in her despatches, and relegated them in tiny versions to the endpapers of the magazine.

Lee Miller in Hitler’s Bathtub, Hitler’s Apartment, Lee Miller with David E. Scherman.

After the war, she returned to England, had a son, got married, and, like many who had spent time at the front, fought PTSD, depression and alcoholism. This wasn’t the end of Miller’s evolution, though. She fought back against her demons, conquered her addiction and tackled what might have been the only creative outlet she hadn’t previously attempted: gourmet cooking. After the war, she attended the famed Cordon Bleu cooking school in Paris and frequently entertained dinner guests with surrealist takes on gourmet meals (dishes like green chicken, blue spaghetti and pink cauliflower figured heavily in her repertoire). She wrote her own recipes and was in the midst of writing a cookbook at the time of her death.

Roland Penrose and Lee Miller, 1965, Cecil Beaton for Vogue. ©The Cecil Beaton Studio Archive at Sotheby’s.

No matter the challenge put before her—someone else ending her flourishing modelling career, a war that tore apart the world, the societal limitations of her gender or a crippling fight against PTSD—Lee Miller always managed to think of a way around the obstacles she faced and found success at any creative endeavour she set her mind to. She may have been born over a century ago, but her life story still inspires and resonates today, and with good reason.

Looking for more Elastic Thinker inspiration? Check out our profiles on Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Dr Seuss, Eduardo Paolozzi and Antoni Gaudi.