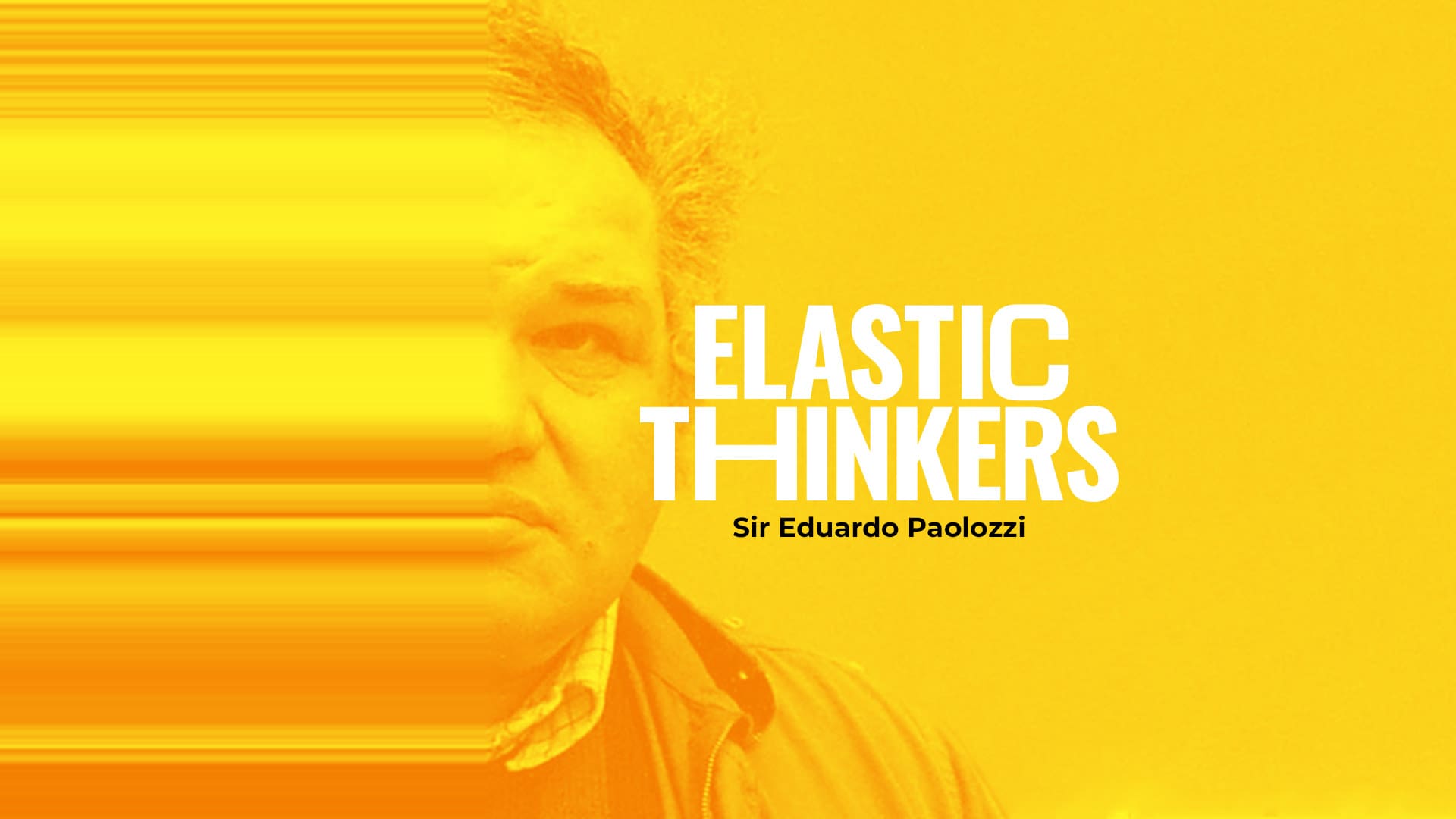

Despite being considered by many to be one of the fathers of Pop Art, Eduardo Paolozzi remains a surprisingly mysterious figure. Andy Warhol popularised Pop Art and his interest in celebrity allowed him to broadcast his message the loudest. But for me, the breadth of work and the investigative thinking that Paolozzi employed have attracted my imagination to a much greater degree. His Elastic thinking was evident from the start—he was always looking, and he never settled for anything less than the best; always reinventing, combining and searching. His artistic travels spanned collage, sculpture and printmaking.

Born in Leith, Edinburgh to a family of Italian immigrants in 1924, he, like many others, was interned for a period during World War II. Further to this, his father, grandfather and uncle were all killed when their ship was torpedoed on its way to Canada. It’s little wonder, then, that his imaginative mind was drawn to and influenced by the ideals of Dadaism and Surrealism. These movements themselves developed out of reactions to war and how it shook humanity. They worked against the neat packaging up of life by the Western world and posited that there was a higher plane of reality that could only be glimpsed in snatches and fragments of dreams. When viewed in the context of Western reason these images and ideas could appear odd or even crazy.

Paolozzi’s murals at Tottenham Court tube station, London.

Not for Paolozzi.

Paolozzi’s signal receptiveness allowed him to mine cultural output and deliver clever imagery juxtapositions. There’s a sense of aesthetic wonder in his textural explorations; the dynamic rhythms he created which are both borrowed and found and made new again by his placement and composition, constantly reframing and reimagining. He had such wide-ranging interests that he worked to fuse together seamlessly: classic and new and antique and throwaway and valuable and cheap, it didn’t matter. He wasn’t afraid to test unlikely objects and reference points and meld them together. His excitement was evident, brimming over with ideas and a love of aesthetic qualities no matter their origin. Model airplanes, children’s toys, electronic circuitry, machinery, jet engines, books and magazines, no matter their origin, dismantled bits and pieces all came together in his mind.

In his rejection of art world norms, it seems clear to me that he would have rejected fame for what it was, too. That’s not to say that he didn’t get noticed, though; some of the more public events in a lifetime of many accolades include:

• He was appointed CBE in 1968.

• In the early 1970s, he became friends with fellow surrealist JG Ballard, author of Crash and Empire of the Sun.

• In 1973, he designed the cover of Paul McCartney’s album Red Rose Speedway.

• In 1982, he created the mosaic tile designs for Tottenham Court Road tube station.

• in 1989, he was knighted by Queen Elizabeth II as Knight Bachelor.

• To this day, several of his pieces remain on public display around Edinburgh. Here at Elastic, we’re fortunate to be right next door to his Millennium Window (2002) at St Mary’s Cathedral.

Cover of Red Rose Speedway, designed by Paolozzi.

Now his genius can be enjoyed and celebrated in the current exhibition I Want To Be A Machine, running at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art. Be sure to also check out Paolozzi’s studio, which is a fascinating frozen record of his thinking process located at the same museum. He surrounded himself with an endless array of found objects and you can just imagine him sitting in the middle of it all, unwrapping his next puzzle.

Looking for more Elastic Thinker inspiration? Check out our profiles on Lee Miller, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Dr Seuss and Antoni Gaudi.